11. University endowments returns

Why are they so different across universities?

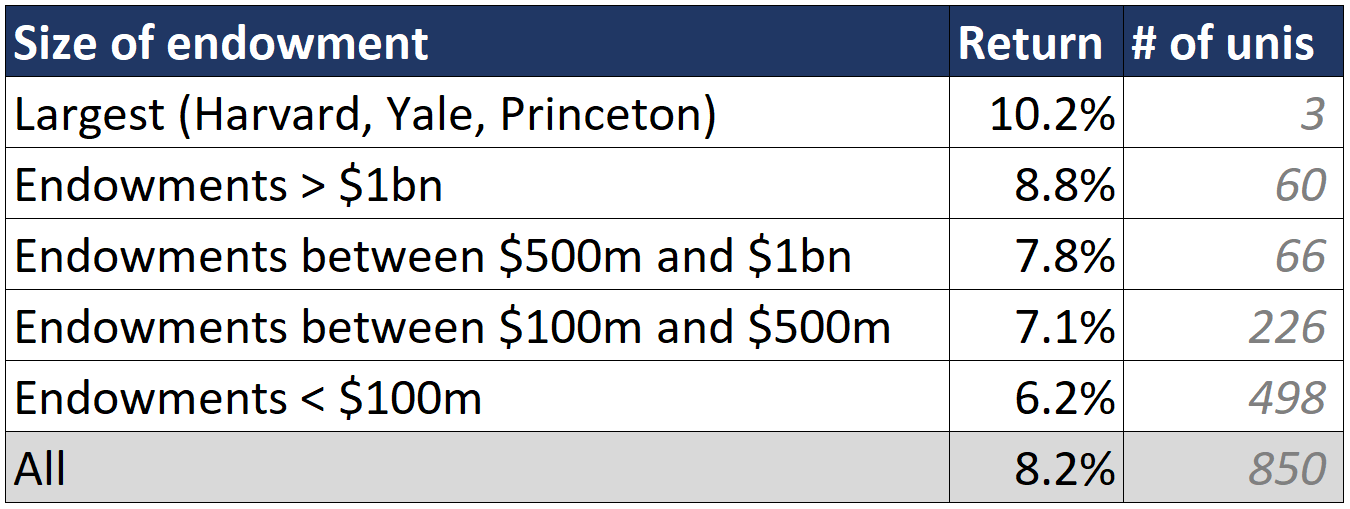

University endowments are a major income source for many of the larger universities, and a considerable proportion of the capital they own. It's very clear there are differences in the sizes of these funds (Harvard: $40bn vs ~500 universities of <$100m), but there are also very significant differences in the returns1 the funds generate:

I didn't realise the gap in rates of return was was so big , and wondered why there’s such a difference.

What are endowments?

Endowments are funds that the university manages. They use these for long term projects as well as filling short term financing needs. On the whole, money is kept in an endowment for as long as possible - withdrawing means sacrificing a potentially larger future return.

The record of endowments for educational purposes traces to Marcus Aurelius, who endowed a chair of philosophy. In the Islamic world, endowments (waqfs) were central to public life. Public institutions such as hospitals, schools and mosques were generally self-sustained by endowments leading to subsidised or free services at the point of use. Many higher education institutions in the Islamic world have been funded by endowments, starting from the 9th century CE.

Endowments have taken a shape of their own with the modern university, especially in the USA.

Where do they get the money from?

Although the initial investment comes from alumni gifts, the larger endowments grow thanks to the return on investment. For the most prestigious universities, only 10% - 20%2 of the yearly increase in fund size comes from alumni gifts. The rest of the accumulation is purely return on capital.

Size determines everything

Answering the initial question - why are there differences in returns for universities?

Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century has an explanation. Smaller funds have a higher proportion of stocks and bonds, whereas larger ones pursue alternative investment strategies - including private equity funds, unlisted foreign stocks and derivatives - all of which require a lot of expertise. The larger funds can pay heftier management fees and gain access to better financial products. For example, if you have a $40bn fund, paying $100m (Harvard’s management bill) in fees is a small investment to generate a more significant return. If the size of the fund is less than $100m - most of them are - you simply can't afford that.

The larger funds grow faster year by year than the total size of the majority of the smaller ones. This will lead to a great divergence in the long run. I’m not going to calculate the expected sizes of these funds in 20 years. There are many factors at play: returns are uncertain, larger endowments may remove more capital to fund a projects, or smaller funds may receive large donations to narrow the gap. Also, some funds have stipulations to pay out a certain percentage every year to avoid capital built up.

What can be done? Perhaps mid-size universities can combine their funds to then access these alternative investment strategies. There are likely to be constrains - e.g. money may be tied to long term investments, or donors may have specified where and how their money can be used. However, it’s an option worth moving towards where possible.

Wider issues

University endowments are just one example of differences in return of capital and there are clearly much wider issues at play. The wealthy have access to instruments that give them better returns on their already larger stocks of capital.

Piketty talks about the divergence in capital ownership that we’re likely to see in the coming century One of his solutions is a wealth tax. Perhaps we’ll explore these ideas in a later post.

Average real returns (after deduction of inflation, admin and financial fees

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Piketty